In 2021, there were 6,576 new cases of gynaecological cancers diagnosed in Australia, and in 2019 there were 1322 new cases of gynaecological cancers diagnosed in New Zealand.

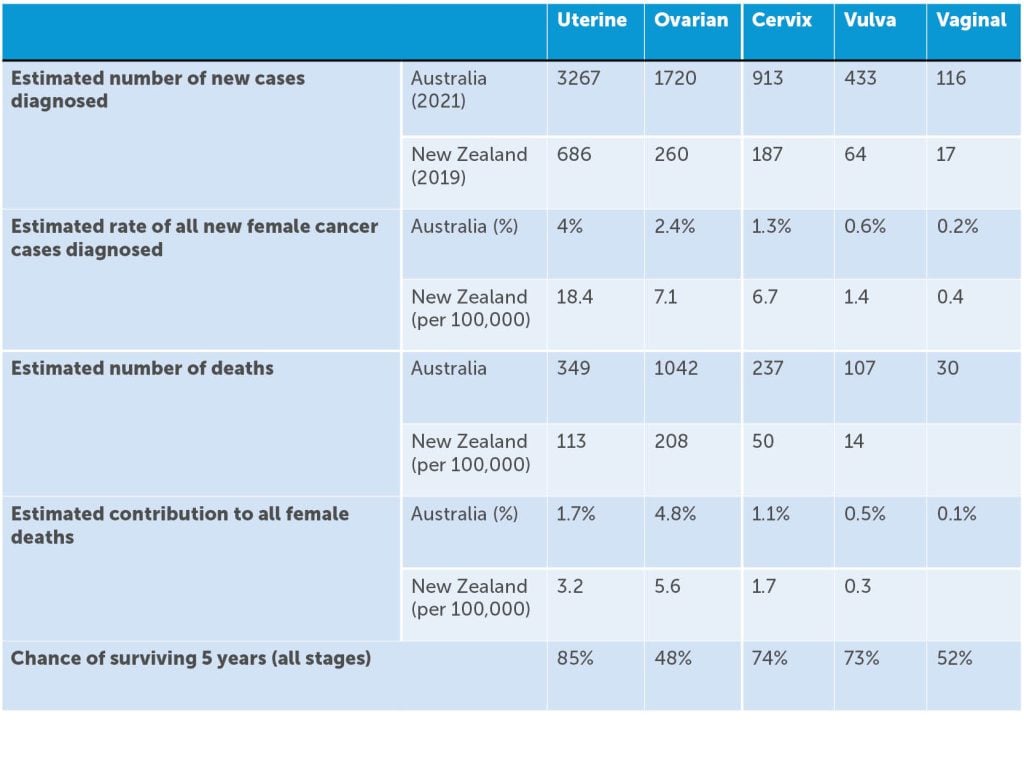

As a group, this represents 9.3% of cancers diagnosed in women, with endometrial cancer being the most commonly diagnosed gynaecological cancer in both countries, coinciding with the worldwide obesity epidemic. It is estimated that an Australian female has a 1 in 23 (or 4.4%) risk of being diagnosed with a gynaecological cancer by age 85. Gynaecological cancer as a group represents 10% of cancer-related deaths in women, with ovarian cancer being the most common cause of gynaecological cancer-related death. With over 21,000 women in Australia living with a gynaecological cancer at the end of 2016 (diagnosed in the preceding five years), there are important survivorship issues to be considered.1 2 (Table 1)

Table 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW)1 data on gynaecological malignancies and New Zealand Ministry of Health.3 4

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the commonest of both the gynaecological cancers and the uterine malignancies, accounting for more than 90% of the latter. Both the incidence and mortality associated with endometrial cancer are increasing in Australia and New Zealand. Obesity, nulliparity and diabetes are all increasing in incidence and are all independently associated with the risk of developing endometrial cancer. Obesity accounts for up to half of all endometrial cancers in high-income countries, and we are no exception. Sixty percent of Australian women are overweight or obese and more than 10% of Australian women have a BMI of 35 or more.5 Furthermore, the fertility rate has fallen in the last decade from 1.9 births per woman to 1.5 and the incidence of diabetes has increased since 2001 to 1 in 5 Australian women.6

The biggest change we are seeing in endometrial cancers is in its classification. We are increasingly moving away from classifying endometrial cancer as type 1 and type 2, as described by Bokhman in 1983, whereby type 1 cancers associated with obesity and metabolic syndromes were considered to have a more favourable prognosis, and those with type 2 cancers, occurring independent of these risk factors, behaved more poorly. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) published a comprehensive genomic analysis of endometrioid and serous endometrial carcinomas in 2013, and we now understand these endometrial cancers to be classified as being a part of four distinct molecular subgroups; POLE ultramutated, microsatellite instability hypermutated, copy-number low, and copy-number high. This molecular classification is increasingly guiding prognostication and the use of adjuvant therapy.7

Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer encompasses the epithelial, germ cell and sex cord stromal histologies, with epithelial cancers being the most common and the most lethal. Ovarian cancer is the ninth most common cancer diagnosed in New Zealand women, and three Australian women die every day from ovarian cancer.8 9 One of the significant risk factors for the development of epithelial ovarian cancer is having a familial cancer syndrome such as a BRCA mutation or Lynch syndrome. While the incidence of ovarian cancer has remained largely unchanged in the last three decades, the age standardised mortality rate in Australia has decreased from 8.8 deaths per 100,000 females in 1982 to 6.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2019.10 Radical surgical management, advances in chemotherapy including the use of intraperitoneal chemotherapy (which may or may not be heated), and molecular targeting agents such as poly adenosine diphosphate–ribose polymerase inhibitors (especially for patients with BRCA mutations) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor inhibitors have likely all contributed to this reduction in mortality.

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is the 11th and 12th most commonly diagnosed cancer in women in Australia and New Zealand respectively, and in both nations represents just over 1% of all gynaecological cancers diagnosed and of cancer deaths in women.11 12 Risk factors for the development of cervical cancer include human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, smoking, number of sexual partners, concurrent immunosuppression including with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and prolonged use of the combined oral contraceptive pill. Persistent infection with high risk types of HPV remains the greatest risk factor for the development of cervical cancer. Both Australia and New Zealand have national immunisation and screening programs to prevent cervical cancer and have seen significant decreases in incidence and death from disease in the last 30 years. The use of population-based HPV vaccination programs is demonstrated to result in reductions in both HPV infections and in the detection of high-grade cytological cervical abnormalities,13 which results in the corresponding reduction in cancer diagnoses and the clear pathway we are on to the elimination of cervical cancer in our nations. If the combined approach of HPV vaccination and co-test screening coverage is maintained at the current rates, cervical cancer is likely to be eliminated as a public health issue in Australia by 2035. Cervical cancer rates will fall below 4 in 100,000 and the associated mortality will fall below 1 per 100,000 women. Despite this there remains challenges, with Māori women and Indigenous Australian women continuing to have a high incidence of, and mortality from, the disease.14

Vulvar cancer

Vulvar cancer is rare and represents about 5% of malignancies of the female genital tract. It includes cancers of the mons pubis, labia majora and minora, clitoris and Bartholin’s gland. Squamous cell carcinomas account for 85–90% of cases, whereas basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, invasive Paget’s disease, Bartholin’s gland carcinomas (where a variety of histologic types may occur), and sarcomas are much less common. Vulvar cancer is typically diagnosed in women over the age of 60 with the highest proportion of cases among women over 80.

The age standardised incidence of vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) has not changed significantly. However, over the past 30 years, HPV-dependent vulva cancer rates have increased by 84% in women under the age of 60. These findings are consistent with an increase in the proportion of HPV-attributable cases of vulvar cancers as a result of changing sexual behaviour in women born from the 1950s onwards, and increased exposure to HPV in this group.15 We are also now seeing that differentiated VIN (dVIN) (HPV-independent and frequently lichen sclerosus associated) has a greater risk of, and more rapid transit to, vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Furthermore, dVIN-associated vulvar cancers have an increased risk of recurrence and higher mortality (93% vs 68% five-year survival)16 than those arising from HSIL, which has changed the way we manage these patients.17

Vaginal cancer

Vaginal cancer is one of the rarest gynaecological cancers and represents 1–2% of malignant neoplasms of the female genital tract. Squamous cell histology accounts for the majority of cases and risk factors include HPV exposure, genital tract dysplasia, cervix cancer and smoking. It is more common in women over the age of 60, however, vaginal adenocarcinomas in particular can occur in younger women, including with in utero DES exposure, which we see infrequently now. Secondary vaginal cancer that arises from metastases elsewhere [cervix (30% cases), endometrium (20%), colon/rectum (10%), ovary (5%) or vulva (5%)] is in fact more common than primary vaginal cancer.

Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

The malignant spectrum of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), collectively called gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN), can arise from any type of viable or non-viable pregnancy and includes invasive mole, choriocarcinoma (CC) and the even rarer placental-site trophoblastic tumour (PSTT) and epithelioid trophoblastic tumour (ETT). GTN occurs in 15–20% of patients diagnosed with GTD and is fortunately highly sensitive to chemotherapy.

Women from Asia and women at the extremes of reproductive age have the highest incidence. In Australia, there is no nationally coordinated program for the registration or management of GTD which makes assessing incidence and trends difficult. There are State-based registries in Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and New Zealand. WA is close to establishment. The Queensland Trophoblastic Centre (QTC) published their experience over a three-year period from 2012–2015. 407 patients were diagnosed with GTD, of which two had PSTT (0.49%), one CC (0.25%), one ETT (0.25%). 41 were diagnosed with persistent disease (GTN) following a molar pregnancy. All women were cured of their disease, however, one woman with underlying anxiety died by suicide at the end of her treatment, giving an overall survival rate of 97.4%.18

Gynaecological malignancies comprise nearly one in ten cancers in Australian and New Zealand women. These women require multidisciplinary care from diagnosis, through treatment, and surveillance. Gynaecological oncologists are available to provide care in all Australian states and territories and across New Zealand.

Our feature articles represent the views of our authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who publish O&G Magazine. While we make every effort to ensure that the information we share is accurate, we welcome any comments, suggestions or correction of errors in our comments section below, or by emailing the editor at [email protected].

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021, AIHW, Australian Government. 2021. doi:10.25816/ye05-nm50

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. New cancer registrations 2019. 2021. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-cancer-registrations-2019

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. New cancer registrations 2019. 2021. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-cancer-registrations-2019.

- Scott OW, Tin Tin S, Bigby SM, Elwood JM. Rapid increase in endometrial cancer incidence and ethnic differences in New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(2):121-7.

- Cancer Council. Obesity trends in Australian adults 2021. Available from: www.obesityevidencehub.org.au/collections/trends/adults-australia

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Births, Australia. Statistics about births and fertility rates for Australia, states and territories, and sub-state regions. 2020. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/births-australia/2020.

- Alexa M, Hasenburg A, Battista MJ. The TCGA molecular classification of endometrial cancer and its possible impact on adjuvant treatment decisions. Cancers. 2021;13(6):1478.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021, AIHW, Australian Government. 2021. doi:10.25816/ye05-nm50

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. New cancer registrations 2019. 2021. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-cancer-registrations-2019

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021, AIHW, Australian Government. 2021. doi:10.25816/ye05-nm50

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021, AIHW, Australian Government. 2021. doi:10.25816/ye05-nm50

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. New cancer registrations 2019. 2021. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-cancer-registrations-2019

- Brotherton JML, Wheeler C, Clifford GM, et al. Surveillance systems for monitoring cervical cancer elimination efforts: Focus on HPV infection, cervical dysplasia, cervical screening and treatment. Preventive Medicine. 2021;144:106293

- Cervical cancer screening and New Zealand’s uncomfortable truths. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):571. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00206-0.

- Barlow EL, Kang YJ, Hacker NF, Canfell K. Changing trends in vulvar cancer incidence and mortality rates in Australia since 1982. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 2015;25(9).

- Eva LJ, Sadler L, Fong KL, et al. Trends in HPV-dependent and HPV-independent vulvar cancers: The changing face of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Gynecologic Oncology. 2020;157(2):450-5.

- Cohen PA, Anderson L, Eva L, Scurry J. Clinical and molecular classification of vulvar squamous pre-cancers. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 2019;29(4).

- Verhoef L, Baartz D, Morrison S, et al. Outcomes of women diagnosed and treated for low‐risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia at the Queensland Trophoblast Centre (QTC). ANZJOG. 2017;57(4):458-63.

Leave a Reply