Female genital tract fistulas are not uncommon in limited resourced areas, in particular, where the provision of emergency obstetric services is under resourced. The Ethiopian1 and Ugandan2 demographic and health surveys states that the percentage of women 15–49 years of age, who experience fistula symptoms are 0.4% and 1.4% respectively. Over 15,500 women in Ethiopia and 18,500 Ugandan women in this age group experience leakage of urine and/or faeces through the vagina. Women with obstetric fistulas suffer from significant mental health and social dysfunction3,4 and ongoing bladder dysfunction.5,6 In Australia, lower urinary tract fistulas (urethro/vesico-vaginal) are often related to gynaecological procedures7 and ano/ rectovaginal fistulas are often due to obstetric and operative aetiologies.8

Lower urinary tract fistulas

In the review of 56 lower urinary tract fistulas repaired by two experienced fistula surgeons (Hannah Krause, Judith Goh) following benign causes/procedures,7 the most common antecedent

events were hysterectomy, urinary incontinence and urethral surgeries and also procedures that may not be considered as associated with fistulas, including suction curettage and cervical cerclage. Although all women presented to the original surgeon with continuous urinary incontinence, only 50% of women were referred by the original surgeon for management of urinary incontinence. Of the 56 women with fistula, two thirds were referred with a diagnosis of fistula and the remaining referred for management of urinary incontinence. In addition, 15 of the 56 women had a recognised intra-operative cystotomy repaired at time of surgery. However, despite this history, the time of original surgery to referral for management was about three months. The mean time from antecedent surgery to referral for management of fistula or urinary incontinence was nearly five months.

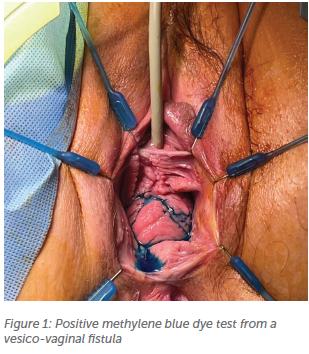

Imaging on these 56 women7 demonstrated 42% positive results from CT cystourethrogram and CT intravenous pyelogram in diagnosing the fistula while cystoscopy had similar results with a 43% positive rate. The dye test was most sensitive in diagnosing the lower urinary tract fistula (Figure 1). The fistula size ranged from 2mm to 4cm (mean 9.75mm) with no clear relationship between size of fistula and positive results from investigations.

All 56 women underwent the vaginal approach for fistula closure via the flap-splitting technique. Fiftyfive women had successful closure of the fistula with the first surgery and the remainder, with a late breakdown three months later, required a second repair, which was successful.1 Over the past two years, the author has repaired another 14 lower genital tract fistulas in Queensland, again hysterectomy being the most common factor. There were also two vesicovaginal fistulas from neglected prolapse pessaries (size of fistula 1cm, 3cm).

Anorectovaginal fistula

Women with anorectal fistulas complain of flatus, mucous and faeces per vagina. For the smaller fistulas, faecal material often passes per vagina when the stools are not well formed. World-wide, obstetric related fistulas are most common. While there are true obstetric rectovaginal fistulas, many women present to fistula units/campaigns with faecal incontinence from chronic unrepaired 4th degree tears.9 (Figure 2)

A review of 41 women who were referred for anorectovaginal fistula management in SE Queensland demonstrated that apart from obstetric and gynaecological aetiologies (including prolapse pessaries), infective and inflammatory conditions play a role in our setting.8 Perianal abscesses might mimic the appearance of a Bartholin’s abscess and incision and drainage in the vagina/labia may inadvertently complete the connection between the anorectum and vagina/perineum, causing a fistula. In five of the 41 cases, these women cited marsupialisation of a Bartholin’s abscess as the procedure related to fistula formation. In this review of the 41 women, faecal diversion did not improve surgical outcomes.8 The average size of the fistula was 11.2mm in diameter (range 2–50mm)

For closure of anorectal fistulas from infective or inflammatory bowel disease, it is recommended that the infection/inflammation is treated in the first instance. It is also generally believed that there is a higher risk of fistula breakdown when the fistula is due to an inflammatory process e.g., Crohn’s disease, and also risk of further fistulas with flare ups of the inflammatory bowel disease even after successful fistula closure.

Principles of surgical management of genital tract fistula

The route of repair of lower genital tract fistulas is dependent on surgeon experience and preference and fistula characteristics. The author’s preference is the vaginal route, even for fistulas at the upper vagina/vault.

Recent urethral/bladder injury with fistula

- • Insert urethral indwelling catheter – the fistula may close spontaneously with prolonged catheterisation (4 weeks)

- If the fistula is established with fusion of mucocutaeous junction, then surgery is required to close the fistula.

- Exclude uretero-vaginal fistula

No inflammation present

- If the injury is recent, with inflammation present, defer the surgery

- If inflammatory bowel disease – medical therapy is required (this may also close the fistula)

Small fistulas – dye test may help locate the fistula in the vagina (Figure 1)

- Ensure the dye is not too dilute; that the solution is dark enough to aid in ease of visualisation of the dye in the vagina

Wide mobilisation of vagina from affected structure (urethra/bladder or ano/rectum)

- Incision made at the muco-cutaneous junction to mobilise the tissues

- The author does not excise any vaginal epithelium as this may cause vaginal stenosis

- Unless the fistula is located at the perineal body, there is NO ‘fistula tract’

- At the edge of the fistula, vaginal epithelium is fused to the urothelium or ano/rectal mucosa

Tension-free closure of the fistula edges

- Do not overtension the sutures when tying the suture knots as this may result in vascular compromise of the tissue

- If possible, a double layer closure

Test integrity of the fistula repair

- The author uses methylene blue for lower urinary tract fistulas and betadine for ano/rectal fistulas

- Dye test also assesses for the possibility of more than 1 fistula

Close the vaginal epithelium

Prolonged indwelling catheter for lower urinary tract fistulas

- Ensure the catheter is secure (usually on the woman’s upper thigh) to avoid pulling/tension on the bladder

Antibiotics

The author does not perform imaging prior to removal of the catheter. A dye test is performed just prior to catheter removal to ensure the fistula is closed, followed by an immediate trial of void.

References

- Ethiopian Bureayuof Statistics: Ethiopina Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; The DHS Program, ICF, Rockville, Maryland, USA, July 2017.

- Ugandan Bureau of Statistics: Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. UBOS Kampala, Uganda The DHS Program, ICF, Rockville, Maryland USA, January 2018.

Leave a Reply