Complications associated with mesh include exposure and erosion of the vaginal wall,1 bladder and urinary tract injuries,2 urinary retention,3 nerve damage and persistent pelvic pain (PPP)2,4 including dyspareunia, and can lead to significant mental health issues for the woman and damaging relationship breakdowns.5 There have been severe depressive symptoms due to the ongoing distress caused by mesh complications including death by suicide.5,6 The physical, mental and financial cost to women due to unsuccessful mesh implantation has been huge.

Evidence tells us that PPP is more effectively treated when a biopsychosocial approach to pain is undertaken.7 Pelvic health physiotherapists in Australia use this best-practice approach in their management plan for PPP by adapting the model extensively researched and taught by Australian physiotherapists and pain researchers, Prof Lorimer Moseley and Dr David Butler.

A biopsychosocial approach includes understanding about the interplay between the biological, psychological and social aspects of the patient’s condition. Understanding the influence of other factors is important for all health professionals involved with mesh patients in order to effectively treat their PPP.

Many women feel injustice with their mesh implant complications. This is due to the initial silence surrounding the issue, the extent of the problem and the ongoing use of mesh for many years despite the compelling evidence to the contrary. The women in the mesh class action legal case in Australia are also facing the distress of reduced compensation payouts due to the large costs subtracted by the legal team who were instrumental in bringing the dreadful stories of these women into mainstream media.8

Factors such as injustice can be measured via the Injustice Experience Questionnaire.9 This has a scoring range between 0–52 (subscales Blame/ Unfairness and Severity/Irreparability) with a score of greater than 30 representing a severe risk of ongoing disability at one year. The injustice suffered by these women has an impact on the severity of their pain. The full recovery of the patient will be stifled if this is not recognised and addressed as a part of the treatment of the patient.

Anger and rumination add to the psychological burden for women who have mesh injuries. The Pain Catastrophisation Scale is a measure of painrelated thoughts and beliefs, measuring rumination, magnification and helplessness. However, currently there are no validated measures that are specifically designed to assess pain associated with pelvic mesh implants. More research is required considering the burden that women have suffered with this catastrophic failure of the healthcare system.10

Social influences such as family, friends and work colleagues and their ability to maintain a relationship with a woman in constant pain are also factors in pain amplification. Health professionals being curious about these impacts rather than dismissive will help with understanding the complexity of a women with persistent pain from failed and problematic mesh implantation.

There is little doubt that the significant complications associated with mesh implantation (such as mesh extrusion and severe pelvic pain) increase anxiety in women.5 Anxiety is associated with adrenaline and cortisol release which can amplify pain. Thoughts are chemical processes and may provoke inflammatory responses in the relevant tissues. Over the years women have formed support groups on Facebook which can be seen both as a ‘saviour’ and ‘escalator’ of their anxiety. When women finally realise the extent of the mesh problems and the number of women affected, they feel validated, and this can be helpful for them. However, hearing the terrible stories of suffering within a group can also be triggering for many women. This contributes to anxiety about their condition, catastrophising, heightened central sensitisation of their nervous system and ultimately may worsen their pain.

The patient’s inability to work because of persistent pain adds to financial distress and heightens anxiety. Some patients incur high medical expensesundergoing the necessary treatment by health professionals for their mesh complications if they are unable to source treatment in publicly funded pelvic mesh centres, adding to their financial hardship.

Physiotherapy assessment of the patient with PPP involves listening to their story. This provides validation to the patient that the therapist before them understands how important their story is to the fabric of their treatment plan and creates a therapeutic alliance with the patient. Baroness Cumberlege in her 2020 UK report on Medical Devices Safety Review ‘First Do No Harm’ said that the system is not good enough at spotting trends in practice and outcomes that give rise to safety concerns. Listening to patients is pivotal to that’.11

Assessing the patient’s urinary system function (with a bladder diary, a pre and post void ultrasound and noting any history of any urinary frequency, recurrent UTI’s, urgency and urinary leakage), bowel function (including regularity, stool consistency, any associated pain and faecal control); sexual dysfunction (pain with sex, fear avoidance of intimacy, loss of sensation and complex feelings of loss of being a ‘broken’ woman associated with their predicament); pelvic nerve pain and referred pain; pelvic floor muscle activity (or overactivity); and their tissue quality, guides treatment strategy selection.

Asking the patient about their goals and expectations from their physiotherapy interaction ensures that the therapist is addressing the patient’s concerns rather than the therapist’s preconceived ideas about what they believe to be important.

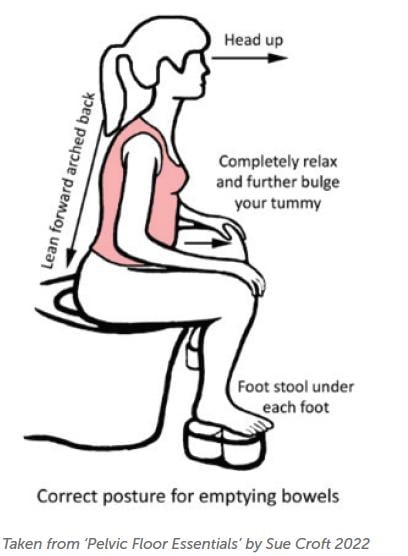

Education is the cornerstone of any pelvic health physiotherapy treatment. Teaching bladder voiding position, efficient pain-free bowel emptying, and good bladder and bowel habits is important to address the biological problems associated with mesh implantation complications.

Bladder residuals leading to chronic urinary tract infections; urinary leakage due to failed effectiveness of sling procedures; overactive bladder leakage; or removal of the offending sling or vaginal mesh leading to the reinstatement of the pre-existing stress urinary incontinence or prolapse are all distressing problems well-served by the conservative strategies taught by pelvic health physiotherapists.

The pelvic floor muscles are often overactive with the patient increasing the muscle tone inadvertently by over-clenching in response to pain, to leakage of urine or faeces or to stress and anxiety. Van der Velde 2001 showed that the pelvic floor muscles behave as ‘first responders’ in response to stress and anxiety, reinforcing the concept that the pelvic floor muscles are hardwired to protect.12 Other muscles in the pelvis can also be implicated. Referral patterns of tension from obturator internus can be seen with other presenting conditions such as coccydynia, Piriformis Syndrome, low back pain and sacro-iliac joint pain among others.

Teaching patients:

- Regular daily pelvic floor muscle down-training.

- Pelvic nerve and pelvic muscle stretches.

- The value of regular belly breathing to enhance the parasympathetic nervous system response over the fight-and-flight sympathetic nervous system upregulation.

- Body scanning to assess muscle tightness and subsequently relaxing the overactive muscles.

- Changing posture into a more slumped and relaxed posture to facilitate abdominal and pelvic muscle relaxation.

These are all invaluable, easy-to-implement treatment strategies which give self-efficacy, and empower the patient to self-manage their pelvic pain more effortlessly.

Woven into the effective treatment of these biological factors is the important concept of teaching effective pain science to the patient. Understanding the concept of central sensitisation is pivotal to explaining how persistent pain upregulates. This involves teaching the concept that pain is not always solely about the issues in the tissues

Measuring the degree of central sensitisation through the validated Central Sensitization Inventory: Part A and Part B (CSI) gives the physiotherapist and the patient insight into the extent of the persistent pain and allows measurement of the progress of the patient with their pain management (if the questionnaire is used regularly).13

Treatment of the sensitised nervous system includes graded exposure to the perceived threat which allows for reorganisation of the sensori-motor cortex through novel non-threatening stimuli and movement. For example, if dyspareunia is an ongoing problem following mesh removal, the pelvic health physiotherapist will teach the patient how to use vaginal trainers (dilators) to allow graded exposure to penetration. The patient will be taught

the importance of good arousal, good tissue quality (from local oestrogen if age appropriate) and the use of an effective lubricant to achieve pleasurable, painfree intimacy.

Health professionals working with patients with persistent pain from mesh implantation must be conscious of the importance of the language and words used. This is fundamental to maintaining a good therapeutic alliance with the patient. Encouraging the patient to be kinder to themselves when they may have a sense of hopelessness from years of persistent pelvic pain is also important when treating pain.

Understanding pain science empowers the patient to have greater autonomy over their treatment process which ultimately helps their financial situation. If the concept of central sensitisation is well explained, it makes complete sense to the patient and can often lead to a faster decrease in pain and symptom resolution increasing the credibility of the physiotherapist. This allows the physiotherapist to assist the patient to change the narrative of their pain story without ever disputing or diminishing the importance of the biological factors at play.

Physiotherapy treatment of PPP associated with mesh implantation decreases catastrophising, empowers women with self-management strategies to treat their pelvic health issues throughout their life and explains why their symptoms can flare unexpectedly despite long periods of improvement with their condition, allowing them to self-manage the flare and return to a high-quality lived experience.

References:

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2(2):CD012079. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012079.

- Kasyan G, Abramyan K, Popov AA, et al. Mesh-related and intraoperative complications of pelvic organ prolapse repair. Cent European J Urol. 2014;67(3):296-301. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2014.03. art17.

- Chughtai B, Mao J, Buck J, et al. Use and risks of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse surgery in women in New York state: population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2685. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2685.

- Abed H, Rahn DD, Lowenstein L, et al; Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Incidence and management of graft erosion, wound granulation, and dyspareunia following vaginal prolapse repair with graft materials: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(7):789-98. doi: 10.1007/ s00192-011-1384-5.

- Dibb B, Woodgate F, Taylor L. When things go wrong: experiences of vaginal mesh complications. Int Urogynecol J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05422-zCc

- Welk B, Reid J, Kelly E, Wu YM. Association of Transvaginal Mesh Complications With the Risk of New-Onset Depression or Self-harm in Women With a Midurethral Sling. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(4):358-360. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4644.

- Mardon A, Leake H, Szeto K, et al. Treatment recommendations for the management of persistent pelvic pain: a systematic review of international clinical practice guidelines (2021) https:// doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17064

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-12-04/mesh-implantclass- action-shine-lawyers-payout-dispute/101728850?utm_ campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_ medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web

- Sullivan MJL, Adams H, Horan S, et al. The role of perceived injustice in the experience of chronic pain and disability: Scale development and validation. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2008;18:249-61.

- Todd J, Aspell JE, Lee MC, Thiruchelvam N. How is pain associated with pelvic mesh implants measured? Refinement of the construct and a scoping review of current assessment tools. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):396. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022- 01977-7.

- First Do No Harm – The report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review Baroness Cumberlege, Sir Cyril Chantler and Simon Whale

- Van der Velde J, Laan E, Everaerd W. Vaginismus, a component of a general defensive reaction. an investigation of pelvic floor muscle activity during exposure to emotion-inducing film excerpts in women with and without vaginismus. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(5):328-31. doi: 10.1007/ s001920170035.

- Neblett R, Cohen H, Choi Y, et al. The Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI): establishing clinically significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J Pain. 2013 May;14(5):438-45. doi: 10.1016/j. jpain.2012.11.012.

Leave a Reply