It isn’t easy practicing urogynaecology these days. None of us entered the practice to cause harm. We understood and regretted transvaginal mesh for primary prolapse. It was not that helpful and potentially harmful, and more importantly, very difficult to remove. However, for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) we have been offering midurethral slings (MUS) since 1998 and we were accustomed to women thanking us for changing their lives and wishing they had had the procedure sooner. After 10 years doing the procedure, we might have come across a patient with severe pelvic or vaginal pain and dyspareunia. Yet the procedure on that patient was no different to the many other cases we performed. That patient weighed heavily on our psyche but did not lead us to feel we should stop offering MUSs as a treatment option. What about all the people that benefitted from the procedure?

Now 20 years later, after the Senate Inquiry of 2018 and the Gill v Ethicon Class Action of 2019, many of our colleagues have stopped operating on women with incontinence for fear of litigation. The remainder of us have widened our skillsets to include treatment options beyond MUSs. Some of us adopted bulking agents, with their variable results (and the women weren’t thanking us as much). Others with a laparoscopic skillset were offering laparoscopic burch colposuspensions. Those without laparoscopic skills moved to open surgery, such as fascial slings.

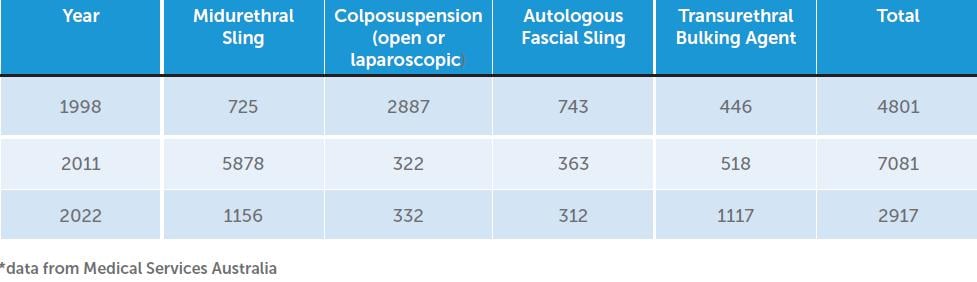

What has followed has been a decline in the number of incontinence procedures. In 2011 there were 7081 continence procedures of any kind performed for stress urinary incontinence in Australia according to the Services Australia Website. By 2022 this number had decreased to 2917 (Table 1). This raises some important and interesting questions. Were women in 2011 being overtreated for mild stress incontinence because MUS was viewed by both surgeons and women as simple minimally invasive low risk procedure. Or are too many women unnecessarily incontinent in 2022 because they or their clinicians are fearful of surgery? I suspect both statements are true.

Back in 1998, when MUS surgery was first emerging as a surgical option in Australia, more than 4800 women had continence surgery, primarily open colposuspensions. This number may be higher if anterior vaginal repairs (with Kelly sutures) are considered, given that this procedure was commonly performed for SUI at the time. For women to decide to undergo a more invasive procedure it is likely that they had more than just mild SUI and were suffering significantly with moderate to severe SUI. Therefore, since 1900 fewer women had SUI surgery in 2022 than in 1998 I suspect there is a sizeable number of women suffering with significant untreated SUI in the community at the moment.

Perhaps women are no longer seeking treatment. Perhaps women have stopped visiting surgeons to manage their stress incontinence in favour of other non-surgical professional groups instead. It is difficult to know for sure because of the lack of formal data on this. I suspect more women are seeking conservative management and accessing pelvic floor muscle training, vaginal devices, extracorporeal magnetic innervation (Emsella chairs) and vaginal laser. To what degree women undertaking such treatments are helped or satisfied with these treatments is unknown.

It is a concern to think that several thousand women every year are remaining incontinent and avoiding surgery because of the fear of mesh, and loss of trust in us as surgeons. We have become tarnished by association with the negative image that mesh now has. The simple logic is, if mesh is bad, and surgeons promote mesh, then surgeons must be bad. We can only help women with pelvic floor problems if we ensure our practice is of a high standard and worthy of the public’s trust in us and our profession.

Surgeons have a responsibility to make women aware of the range of approaches that can be offered to manage their incontinence, including pelvic floor muscle training, intravaginal devices such as continence dishes and contiform devices, as well as surgical approaches. When a surgical approach is discussed, women should be given the ACSQHC information sheet, and summary data comparing surgical procedures. They should be given the chance to read these and other resources in their own time and return for a subsequent consultation to have their questions answered and be allowed to choose the procedure they want. If their preference is for a procedure that their surgeon is not trained to perform, that surgeon should refer the woman to a colleague that can perform that procedure. In the meantime, such surgeons need to expand their skillset to encompass other minimally invasive procedures such as laparoscopic burch colposuspension, and begin teaching their trainees. In this way, one woman at a time, we might help restore women’s confidence in us, and be an ongoing help with their continence issues.

Mesh sacrocolpopexy (Mesh SCP) has been the goldstandard procedure for apical pelvic organ prolapse since the operation was first described in 1957. It was not mentioned in the Senate Inquiry, it is reserved for women with the most severe prolapse. Yet access to mesh for such women is being compromised. The absence of mesh as an option for such women would put them at higher risk of suboptimal outcomes.

In 2019 (before Covid) there were 824 cases performed in Australia compared to over 16,000 vaginal prolapse cases. The lack of access to mesh could not have come at a worse time. By 2022 the cases of sacrocolpopexy had decreased to 598. Surgeons have been forced to perform colpocleisis procedures in women who otherwise might have wanted to retain sexual function. These colpocleisis procedures increased from 127 women in 2019 to 218 cases in 2022 (Services Australia Website). Some surgeons are using fascia lata or cadaveric material, though such products may not be as robust as mesh and carry morbidity from leg incisions.

The problems with mesh access for sacrocolpopexy have been even more complex than for MUS. To summarise, the TGA upgraded the classification of meshes from class II to class III in 2018. International companies such as Coloplast, Boston Scientific, and Ethicon, were therefore required to provide further data, at a greater cost, to justify keeping their meshes on the theatre shelves for this procedure. All companies withdrew their products leaving none available for women needing sacrocolpopexy. At the time of the TGA request, no other country had asked such companies to justify their products, but many of these companies are now having to make similar efforts to keep their products in Europe and hopefully might rethink their decision to abandon Australia in the future.

Because of the actions of the TGA and mesh companies, there is currently no Class III mesh available on the shelf for women needing sacrocolpopexy in either Australia or New Zealand. This is a desperate situation considering this procedure is treating the women with the worst prolapse. Even the UK (which has paused MUS) still has access to these products. Only one product designed and marketed for sacrocolpopexy is available, but this is not on the Register of Therapeutic Goods and is available only via the Special Access Scheme. The situation is worse in New Zealand where there is no Special Access Scheme product available. In Australia, the product TiLOOP (pfm GmBH) is attempting to achieve Class III status, but is awaiting European CE approval outcomes before applying to the TGA. If successful, it will be the only sacrocolpopexy-specific product available to women.

One other reason for the lack of access to mesh (and hence the decline in SCP cases), at least in the private sector, is resistance from health insurance providers. In the private sector, surgeons are receiving SAS approvals for TiLOOP, but insurance companies are refusing to pay for the product because it is not on the Register of Therapeutic Goods. It is theoretically possible that some surgeons in the private sector are using generic class III hernia mesh off the shelf and off label for the sake of their patient, but at their own risk. Calls from the TGA to insurance companies have fallen on deaf ears.

Another reason for the decline in SCP cases is fear of mesh by women and their families. A patient I recently saw had recurrent apical prolapse seven years after I had performed a vaginal hysterectomy and sacrospinous fixation. On examination she had a narrow vagina not amenable to vaginal devices or repeat vaginal surgery or colpocleisis. I offered a laparoscopic mesh sacrolpopexy. I did not think fascia lata would do an adequate job in her case as it would only support the anterior compartment; however, I did not offer this as an option. I described the mesh procedure and went through a dedicated consent document with her word for word. She took the idea home to her family who immediately banned her from proceeding without wanting to discuss this further. The family decided that mesh is bad, and that since I offered it, I must also be bad. Anything I said after that would not be trusted. Sadly, the patient will live with the problem. My lesson in her case was that I should have offered a non-mesh option during the consultation and offered her choice after adequately discussing the pros and cons. Had she chosen a non-mesh procedure knowing it was inferior, I would have to honour her choice. There is no room for paternalism if there is no trust by patients. Not offering the non-mesh option because I believed it was inferior was a paternalistic value judgment. I sent her the latest RANZCOG guideline on Sacrocolpopexy, but it will carry little influence. RANZCOG continues to be called to account. In 2022 the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality asked for credentialling statements to limit who can perform sacrocolpopexy procedures.

In 2023 the Prosthesis List Committee has asked RANZCOG for comparative and cost data on the various continence procedures, and the ACSQHC want a model of care for sacrocolpopexy. In New Zealand, a petition is being brought to parliament requesting a suspension of midurethral slings. Furthermore, NZ gynaecologists wanting to perform incontinence and some pelvic floor surgeries (not just mesh cases) are currently undergoing a rigorous credentialling processes, which stand to limit their ability to perform some surgeries if they do not meet the criteria. What is happening in New Zealand could easily happen in Australia.

So where did we go wrong?

The health regulatory system allowed the proliferation of mesh products which were rapidly adopted by surgeons internationally. Why? Because for MUS they offered a simple, elegant, effective, and minimally invasive solution to a common problem. This happened organically without clinical trial evidence, ongoing surveillance systems, formal training programs, or prospective data collection and review (clinical registries). Adverse outcomes were uncommon and sometimes occurred sometime after surgery, meaning the operating surgeon was often unaware of problems or did not connect the symptoms with the original surgery.

What have we learnt from our experience with mesh?

We now know that high-quality research is just as important for surgical innovation as it is for other treatments. We have re-learnt the importance of surgical data and follow up in uncovering problems. We better understand the importance of surgical training for new procedures, the importance of patient selection, communication skills and detailed broad-based, procedure specific informed consent. These lessons need to be applied to all novel treatments in the field of urogynecology and beyond.

What should we do now?

- Prospective documentation of surgery. I would advise that every RANZCOG member that sees and treats women with urinary and pelvic organ prolapse begin documenting every single case they see. I would recommend making a database, including evidence of the first treatment steps such as whether a pessary was trialled. It is important that our critics understand that we see the vast majority of women with pelvic floor disorders, and that a majority of women receive conservative care, and that we are not operating on every woman we see. We treat these conditions holistically, not just surgically. By keeping our data, each of us will demonstrate that as gynaecologists we are champions for pelvic floor problems. This is a tall ask, but our specialty is encountering hostile times. The denominator will be important when we show we treat 50% of our patients conservatively, and might insert mesh in, perhaps 1 or 2 of 10 of the women we saw, and that we performed non-mesh vaginal surgical procedures in 2 or 3 of those 10 women. Trainees should do the same, and keep that data forever, because evidence of training is fundamental in protecting ourselves against future challenges. It’s tedious but it is worthwhile.

- Record outcomes including PROMs and report problems. I also suggest that PROM measures be routinely used for all your procedures at six weeks and six months. Log these on a database also. For those without their own established databases, The Australasian Pelvic Floor Procedures Registry was initiated in January 2021 and holds data reported by clinicians across Australia that contains validated PROMs and is accessible to the TGA for early detection of problems with particular meshes or grafts. In this way, my rare complication and another surgeon’s rare complication can be mapped, and the detection of problematic products can be identified earlier to keep our patients safe. If as surgeons we are promptly made aware, action might then be taken by our own specialty, rather than social media, government, and law courts. Go to www.apfpr.org to register. Furthermore, read the ACSQHC guidelines on credentialling for SUI and sacrocolpopexy. A model of care for sacrocolpopexy is also under way.

- Discuss and document all options. Offering pelvic floor muscle training options and vaginal devices for continence or prolapse is a routine part of the education and treatment of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Devices for continence (such as continence dishes and contiform devices) and for prolapse (rings, shaatz, cubes, gellhorns etc) should be routinely considered and offered. It is insufficient to offer only ring pessaries. My practice is stocked with a range of devices. An alternative would be to refer to a clinician near you that can provide and fit these devices if women are inclined. All of us who treat pelvic floor conditions understand that surgical options should be considered once conservative approaches have been explored and are problematic, or if women chose not to use vaginal devices. These options should be documented. If surgery is needed, even if you think a mesh option is best, make sure nonmesh options are discussed. Our patients should be given options and choices.

- Expand your surgical skillset. Pelvic floor surgeons need to either expand their skillset to include minimally invasive procedures such as laparoscopic burch colposuspension/ or pectopexy, and make sure these options are offered. Referral to colleagues that do procedures that we can’t might be difficult for the ego, but it is necessary if our specialty is to rebuild its reputation in the public eye.

- Detailed standardised consent. If a woman chooses a mesh procedure, it is important to sit and read pre-written standardised information about the procedure with the patient. A consent should include the word ‘mesh’ so that there is no doubt that the patient understands this issue. If it is off label, this too should be written on the consent. Provide the IFU (information for use) document to the patient, and the patient batch number after the procedure. In the near future, unique device identifier labels will be developed for every device.

Leave a Reply