Newborn jaundice, or neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia, is a common condition characterised by increasing levels of bilirubin, which manifests as visible yellowing of the skin and mucous membranes. This condition often arises due to physiological changes that occur in the first few days to weeks of a newborn’s life. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the identification, diagnosis and treatment of newborn jaundice, along with emerging trends in management.

While jaundice itself is often benign, resolving with time and effective feeding, there is a subset of infants that have underlying pathology that requires further investigation and management. These infants are identified through risk stratification, their feeding capabilities, background risk factors, circumstances surrounding birth and investigations reserved for those with factors or propensity for pathological jaundice. Treatment choices are broad and are utilised depending on the levels and degree of change in serum bilirubin. Inpatient phototherapy is often the first line of treatment. However, as will be discussed, many infants are able to be managed with conservative, non-invasive treatments. With point of care diagnostics, phototherapy at home is quickly evolving as a cost-effective and minimally invasive treatment to minimise separation of mum and baby.

Bilirubin is a result of heme breakdown, a component of red blood cells (RBC) necessary for oxygen transport. The liver is responsible for enzymatic breakdown of bilirubin, which is then excreted through the gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) tract.

Jaundice is frequently encountered in physiologically normal neonates due to:

- increased RBC (and therefore heme) mass¹

- shortened RBC lifespan (60–90 days in term infants compared with 120 days in adults)²

- reduced hepatic enzyme activity responsible for bilirubin breakdown (1% activity compared with adults)²

- reduced gut bacteria capable of breaking down bilirubin in sterile guts,² leading to increased reabsorption of bilirubin

Jaundice reflects an imbalance between breakdown and effective excretion of bilirubin, representing excess bilirubin deposition in peripheral tissues and mucous membranes. In neonates, this classically progresses in a ‘head-to-tail’ (cephalocaudal) pattern; however, this is not indicative of serum levels of bilirubin and cannot guide subsequent management.

When bilirubin levels rise, binding proteins in serum such as albumin lose their ability to bind bilirubin, leading to increased ‘free’ bilirubin. This unbound bilirubin can cross the blood-brain barrier and can cause direct damage to neurons. This can lead to irreversible neurological damage, collectively known as bilirubin-induced neurologic disorders (BIND) and formerly known as kernicterus. BIND is a broad diagnosis, with long-term symptoms reflecting the regions that were most severely affected by bilirubin, and can include visual, hearing, gait, speech, language and cognitive delays. Consequently, identifying babies with rising serum bilirubin and starting appropriate treatment is crucial for preventing BIND.

A critical part of reviewing jaundiced newborns is separating benign jaundice from causes requiring close investigation and prevention of BIND. Despite the increased bilirubin breakdown and reduced clearance capacity, neonates do not reach peak serum bilirubin levels until 48–96 hours,² and visible jaundice should generally resolve by 14 days.² Early identification involves separating benign jaundice from cases requiring in-depth investigation to prevent BIND. Newborns with jaundice appearing within the first 24 hours or persisting after two weeks require further evaluation.

In cases of mild physiological jaundice, one of the most effective ways in overcoming increased bilirubin is assisting movement of bilirubin through the GI tract. Increasing feeds fosters bacterial growth in the GI tract, which assists in breaking down bilirubin and reducing recirculation, both through formula or breast milk. If breastfeeding is not sufficient, supplementation with formula or pasteurised donor milk can help improve GI function and reduce bilirubin reabsorption. In a smaller cohort of newborns, intravenous hydration can also be used as an adjunct to facilitate further ‘flushing’ of bilirubin through GI/GU tracts.

If a baby has measured bilirubin levels that require treatment, has risk factors for developing jaundice as described in Table 1, or are associated with symptoms that could be suggestive of high bilirubin (such as poor feeding and not waking for feeds with observed jaundice), then phototherapy is first-line treatment.

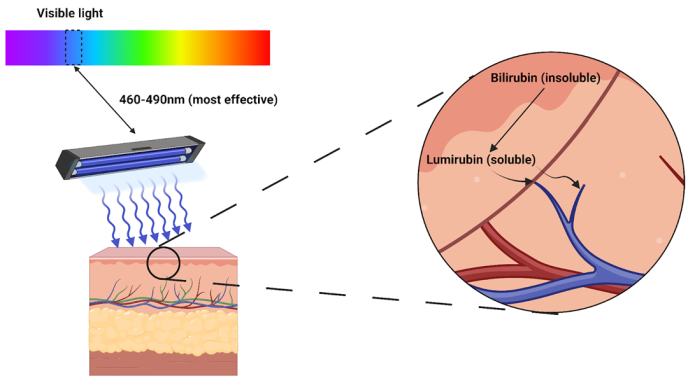

Phototherapy uses blue light therapy to convert bilirubin into the soluble by-product lumirubin through absorption of light into the skin (Figure 1). Lumirubin is both non-neurotoxic and more effectively cleared by the body than bilirubin, being excreted both in urine and the GI tract.

| Risk Factors | Diagnostic tests |

| Birth trauma (eg cephalohaematoma) |

Blood group and Coombs test |

| Prematurity (<35 weeks) | Blood film for RBC morphology |

| Family history of haemolytic disorders |

Infective screen |

| Rhesus incompatibility |

Table 1. Common risk factors and diagnostic tests for newborn jaundice.

In select, severe cases of hyperbilirubinaemia with concern for BIND, exchange transfusion is utilised, where a newborn’s entire blood is replaced in small aliquots with donor blood, to remove bilirubin. This is a manually performed and a high-risk procedure, which although effective, is not as readily used in practice. By increasing skin exposure and the number of lights, phototherapy can often be more effectively performed, such that ‘high intensity’ phototherapy is often utilised in early stages to prevent the need for exchange transfusion.

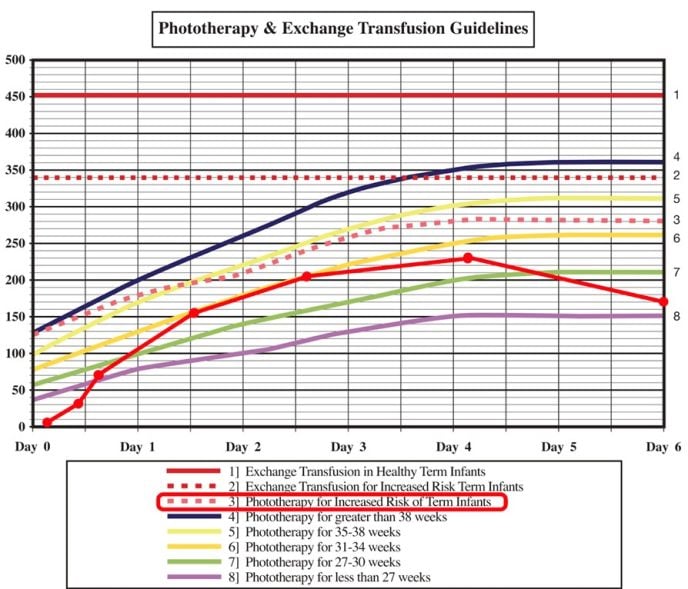

On commencement of inpatient phototherapy or with clinical concern, babies will have serial measurements of bilirubin (Figure 2) and will be ‘weaned’ with periods off light to assess their capacity for bilirubin breakdown, monitoring for periods of ‘rebound’, and facilitate transition to home.

Recent developments in treatment

For low-risk newborns with bilirubin levels close to treatment thresholds, several centres can offer home phototherapy. This has numerous potential benefits, including improved early newborn-maternal bonding, decreased hospital bed occupancy rates and potentially lower overall costs of treatment.

Designs and techniques differ between hospital regions, but in general, families are counselled on the use of a portable phototherapy device, with babies wrapped in them, with short breaks for feeding, settling and care.

To ensure effective treatment of jaundice, families will be visited daily by community practitioners where point-of-care (POC) devices such as a transcutaneous bilirubinometer (TcB) are used. This device uses optical spectroscopy to analyse the amount of light absorption from the device by bilirubin into the skin and has been shown to be a highly sensitive screening tool for ruling out hyperbilirubinaemia in newborns.³ The limitations of these devices are their accuracy in infants with darker skin tones, their accuracy at higher bilirubin concentrations and they are unreliable once a biliblanket has been used,⁴ so confirmatory testing with serum bilirubin levels is required in these cases.

Figure 1. Overview of phototherapy. The use of blue light (with specific wavelengths as described) facilitates isomerisation (or transformation) of bilirubin into lumirubin, a substance capable of direct excretion in GI/GU tracts. Adapted from ‘light’ by BioRender.com (2023), available at https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates.

Figure 2. Example of inpatient bilirubin monitoring using a standardised nomogram. This 38-week macrosomic baby was born by ventouse and sustained a significant cephalohaematoma, thus monitoring their levels accordingly by line ‘3’. Concern for increasing jaundice and poor feeds lead to close bilirubin monitoring. They were discharged on the fourth day of life and had a follow-up heel prick bilirubin on day 6 with improving bilirubin levels, without further follow up. Adapted from Tasmanian Health Service South Guidelines, 2023.

If there are concerns of worsening jaundice demonstrated with the TcB, a formal bilirubin test via heel prick is generally performed and discussed with local paediatric/neonatal teams for further decisions. Studies of wide-scale home phototherapy have shown it to be an effective method to keep babies at home, with Australian statistics showing a $2 million saving with 2 weeks of midwifery-at-home care compared with a 2-day, inpatient phototherapy admission among a cohort of 4038 infants.⁵ Given its cost-effectiveness, home phototherapy will likely become a main form of treatment for low-risk babies with physiological jaundice requiring treatment.

Newborn jaundice is a condition encountered in newborns, commonly due to physiological transitions and, rarely, pathological processes. Benign jaundice is often self-resolving with time and increased feeds, whereas jaundice in at-risk babies or with a pathologic origin requires investigation and close observation. Clinical examination cannot determine the level of jaundice in a baby, and babies with jaundice in the first 24 hours or persisting after two weeks require urgent/close reviews, respectively. Phototherapy and regular feeding continue to remain the most effective way to assist babies in offloading bilirubin. Home phototherapy with POC diagnostics is a highly cost-effective and rewarding technique to foster maternal-infant bonding and will likely become a key method of care for low-risk neonates needing ongoing jaundice management.

References

- Jopling J, Henry E, Wiedmeier SE, Christensen RD. Reference ranges for hematocrit and blood hemoglobin concentration during the neonatal period: data from a multihospital health care system. Pediatrics 2009;123(2):e333-7. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2654

- Gleason CA, Juul SE. Avery’s diseases of the newborn. Elsevier; 2023.

- Okwundu CI, Olowoyeye A, Uthman OA, et al. Transcutaneous bilirubinometry versus total serum bilirubin measurement for newborns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023;5(5):CD012660. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012660.pub2

- Casnocha Lucanova L, Matasova K, Zibolen M, Krcho P. Accuracy of transcutaneous bilirubin measurement in newborns after phototherapy. J Perinatol 2016;36(10):858–861. doi:10.1038/jp.2016.91

- Khajehei M, Gidaszewski B, Maheshwari R, McGee TM. Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of large-scale midwifery-led, paediatrician-overseen home phototherapy and neonatal jaundice surveillance: a retrospective cohort study. J Paediatr Child Health 2022;58(7):1159–1167. doi:10.1111/jpc.15925

Leave a Reply