With an evolving patient cohort and the rise in use of technology, medicine in the 21st century is rapidly changing. This change in patient cohort extends to those seeking specialist gynaecological opinion and care, with the presence of more complex co-morbidities, increased age, particularly in the setting of fertility optimisation, as well as the increased incidence of metabolic disorders.1

As clinicians, we can use comprehensible score calculator applications to optimise and assess our patients for gynaecological surgery. Below are discussion points regarding risk calculators for malignancy, morbidity and mortality, as well as tools that can guide surgical complexity and patient expectations of outcomes from surgery.

For many of these calculators discussed, there is no substitute for collection of information through thorough clinical history, examination and gathering of investigations. Once the above has been collected and surgery deemed an option for management, appropriateness for surgery must be established, including individual patient factors and surgical planning by the operating team.

A common referral to gynaecology services includes the management of adnexal masses. A useful tool for calculating the likelihood of the mass being malignant is the Risk of Malignancy Index (RMI). The RMI requires the following information to identify risk of malignancy; post-menopausal status, ultrasound features of the mass and serum Ca-125 level. A RMI >200 is considered high risk for malignancy and yields a 71% sensitivity and 92% specificity for ovarian cancer.2 By calculating an RMI as part of preoperative workup for adnexal masses appropriate referral can be made to gynaecology oncology services when a lesion is deemed high risk for malignancy.3

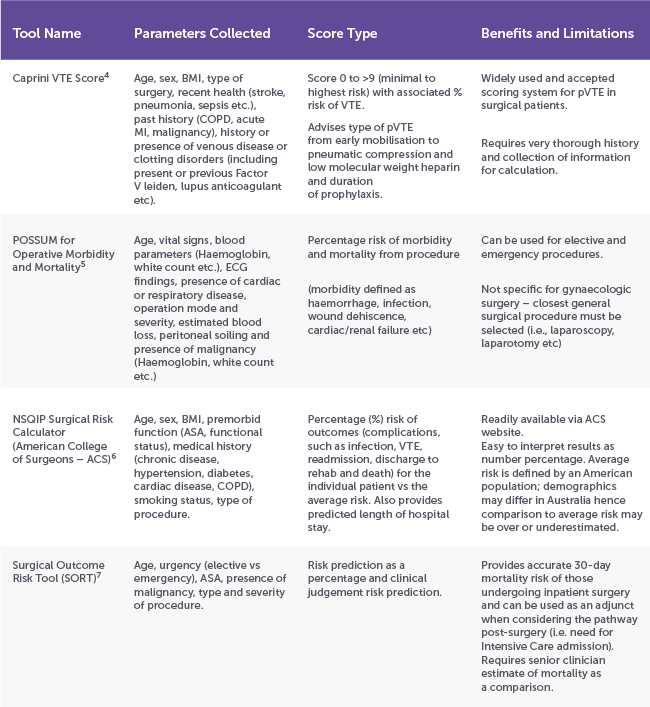

Once a gynaecological diagnosis has been made or suspected, patient suitability for surgery should be assessed. With our ageing and increasing comorbid population, morbidity and mortality needs to be considered and discussed with patients, particularly those with higher risk factors such as metabolic disease, respiratory disease and history of venous thromboembolism (VTE). The below table is a summary of easily available calculators (most are available via an app or web browser) that can be utilised as both discussion points when counselling patients for gynaecological surgery and to highlight areas for peri-operative management, such as post operative destination (i.e. intensive vs ward care) and timing and duration of VTE prophylaxis.

Noting the limitations of each calculator listed above, most scores provided are a simple and accurate way to outline the risk of morbidity and mortality for each individual patient prior to their surgery which can be used as discussion points during the consent process.

A tool that can be utilised by clinicians for assessment of surgical complexity for endometriosis includes the American Association of Gynaecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) 2021 Endometriosis Classification. Multiple endometriosis classification systems have been proposed and used in the last 40 years, with the most utilised being the 1996 American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) classification system8, which provides I-IV staging (mild – severe) and is widely accepted and easy for patients to understand9.

However, the ASRM classification imperfectly correlates to the extent of endometriosis, pain and infertility9 and poorly correlates to surgical complexity, hence is limited in use for clinicians to objectively evaluate surgical complexity.8 The 2021 AAGL Endometriosis Classification was created to help identify objective intraoperative findings that discriminate surgical complexity better than the ASRM staging system which can help clarify communication in medical records and aid future clinical research8, especially in the setting of more severe endometriosis (AAGL 2 and above). It is worth noting however that both ARSM and AAGL classifications have limitations in reference to pain, especially non-cyclical pelvic pain, where higher score does not necessarily correlate with more perceived pain, further demonstrating the wide variety of presentations of endometriosis.10

The above calculators and tools are not an exhaustive list of applications that can be used for preoperative planning and assessment prior to gynaecological surgery but are a guide to the variety of tools that are readily available via applications for clinicians and patients to utilise. It is worth keeping in mind that most of the calculators available are not a substitute for clinician determined indication for surgery but are helpful adjuncts when discussing the risks of proceeding to surgery, helping to inform valid expectations of outcomes for patients and to guide clinical optimisation prior to proceeding with surgery.

References

- Elsherbiny M, Tsampras N. Modern considerations for perioperative care in gynaecology. Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. 2022;32(2):14-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogrm.2021.12.003

- Tingulstad S, Hagen B, Skjeldestad FE, Halvorsen T, Nustad K, Onsrud M. The risk-of-malignancy index to evaluate potential ovarian cancers in local hospitals. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Mar;93(3):448-52. PMID: 10074998

- Management of suspected adnexal masses in perimenopausal women. RCOG Green Top Guideline 62. Published November 2011. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/yhujmdvr/gtg_62-1.pdf

- Caprini JA, Arcelus JI, Hasty JH, Tamhane AC, Fabrega F. Clinical assessment of venous thromboembolic risk in surgical patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1991;17(3):304-12. PMID: 1754886.

- Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M. POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg. 1991 Mar;78(3):355-60. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800780327. PMID: 2021856.

- Liu Y, Ko C, Hall B, Cohen M. American College of Surgeons NSQIP Risk Calculator Accuracy Using a Machine Learning Algorithm Compared with Regression. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2023; 236(5): 1024-1030. DOI: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000556

- Protopapa KL, Simpson JC, Smith NC, Moonesinghe SR. Development and validation of the Surgical Outcome Risk Tool (SORT). Br J Surg. 2014; 101(13):1774-83. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.9638

- Abraro M, et al. AAGL 2021 endometriosis classification: an anatomy-based surgical complexity score. JMIG. 2021; 28(11): 1941-1950. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2021.09.709

- Haas D, et al. The rASRM score and the Enzian classification for endometriosis: their strengths and weaknesses. AOGS. 2012; 92(1): 3-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12026

- Fauconnier A, et al. Relation between pain symptoms and the anatomic location of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 2002; 78(4): 719-726. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03331-9

Leave a Reply