We’ve come a long way… or have we?

Emergency contraception (EC) has come a long way since the days when Family Planning clinics and other services provided cut-up sections of pink oral contraceptive pill strips and a dose or two of an antiemetic in tiny sealed plastic bags to women who were lucky enough to know about this option.

When evidence demonstrated the superiority of the progestogen-only regimen in 19981, these plastic bags were then loaded with 50 minipills – many more pills to swallow but less nausea and vomiting for these women ‘in the know’. However, despite current ‘over the counter’ (OTC) availability of a dedicated product and clear evidence on its safety and efficacy, it is probably underutilised and poorly understood by many in the community and by some health professionals.

EC is defined as a medication or device used to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse (including sexual assault) or after a recognised contraceptive failure. It has alternatively been called postcoital contraception or ‘the morning after pill’. These terms are confusing and imply that EC pills can only be taken immediately, which is incorrect. They can be used, while with decreasing efficacy, for up to five days post intercourse.

There are no evidence-based absolute contraindications to hormonal EC except established pregnancy (due to a lack of efficacy rather than specific adverse outcomes) and allergy. Side effects are uncommon with the progestogen-only regimen and hormonal EC can be used more than once in a cycle if required. It will not provide protection for the rest of the cycle, so ongoing contraception should be addressed from the time of administration.2

What is used in Australia?

The oldest method of hormonal EC, the ‘Yuzpe’ method (named after the Canadian who described it), was introduced in 1974 and consisted of two doses of 100mcg of ethinyl estradiol and 500mcg of levonorgestrel, given 12 hours apart. Only a few countries ever licensed this method, but it was widely used off-label, including in Australia. It is associated with side effects, particularly nausea and vomiting, due to the high estrogen dose and was therefore usually administered with prophylactic antiemetics.

The progestogen method, using levonorgestrel (LNG), was found to be both more effective and associated with less side effects in a WHO study.1 LNG is administered in two doses of 0.75g 12 hours apart, or a single dose of 1.5mg is equally effective for EC.3 Until 2002, there was no prescribable EC brand in Australia, so LNG EC was given off-licence as two doses of 25 minipills (this was understandably sometimes viewed by women with great trepidation). Postinor-2® became available on prescription in mid 2002 and then was rescheduled in January 2004 as a pharmacy supplied product. Since then, three other brands have been marketed – Levonelle-2®, Norlevo® (both containing two 0.75mg tablets) and more recently Postinor-1® which delivers the 1.5mg as a single tablet.

The other available method of EC is insertion of a copper bearing intrauterine device (IuD) within five days of unprotected intercourse (uPSI). While an IuD is highly effective4,5 and has the advantage of providing immediate ongoing contraception, insertion needs to be done by a skilled medical practitioner. Historically, services able to provide IuD insertion within this timeframe are very limited in Australia, so this in practice is a rarely used option. It should be noted that insertion of a LNG IuD (Mirena ®) cannot be used as EC as it is not effective for this indication.

Other regimens available elsewhere

The antiprogestin, mifepristone, has been studied as an EC and is used in some countries for this indication. A Cochrane review5 found mid-dose (25 to 50mg) mifepristone to be superior in efficacy to other hormonal regimes and low-dose (less than 25mg) to be at least as effective as the commonly used LNG 1.5mg regime. ulipristal, a selective progesterone-receptor modulator, has recently been marketed as EC in Europe. A randomised study comparing ulipristal with LNG as EC, found it to be more effective overall and to have higher effectiveness between 73 and 120 hours after uPSI.6

Efficacy

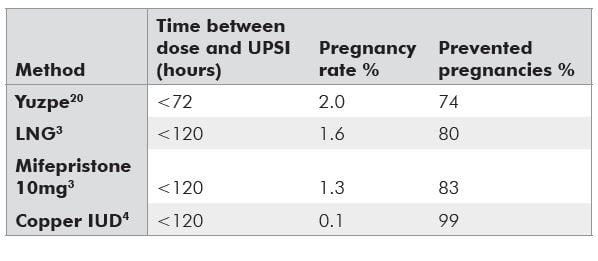

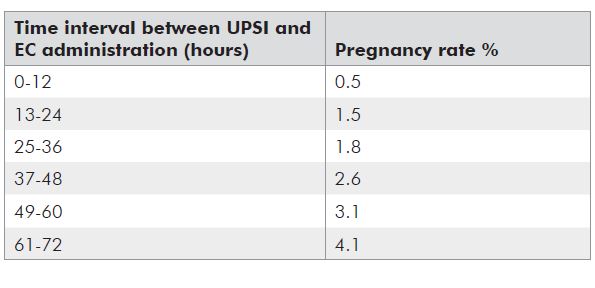

Currently used hormonal methods of EC prevent about 50 to 80 per cent of pregnancies.7 Efficacy rates for EC are estimated by comparing the number of pregnancies observed among a large number of women using the EC method to the number of pregnancies that would be expected in an equivalent number of women with the same coital history, but using no contraception, and is expressed as a percentage. The number of ‘expected’ pregnancies is based on a series of calculations based on numerous assumptions and suffers from the imprecision with which the day of ovulation can be known in any woman.8 The generally quoted efficacy rates (see Table 1) have been criticised as an overestimate and several recent investigators have attempted to recalculate the efficacy, suggesting that EC prevents, as a minimum, 50 per cent of pregnancies.8 It is known that efficacy for hormonal methods decreases with lengthening interval of administration after intercourse (see Table 2). This is not the case for a copper IuD, which is equally effective any time up to five days post intercourse.

Table 1. Efficacy rates for emergency contraception methods.

Table 2. Pregnancy rates relative to timing.9

Mechanism of action

Possible reproductive targets for EC include follicular development, ovulation, sperm transport, fertilisation, implantation and corpus luteum function. As sperm are viable in the female reproductive tract for up to five (or sometimes seven) days, while ovum can only be fertilised within 24 hours of ovulation, the mechanism of action most likely differs depending on when hormonal EC is given in relation to the time of intercourse and the time of ovulation.10 Research has shown that the primary mechanism of action is by the prevention or postponement of ovulation through its effect on the LH surge10, but that this will work only if given at least two days before ovulation.7 The overall biological data overall strongly suggest that the most likely mode of action is thus prefertilisation. This is supported by (and explains) the reducing efficacy rates with greater time interval between coitus and administration described above. That is, the later hormonal EC is given, the more likely it is that the LH surge has already occurred and ovulation will not be prevented. There is no data to support the view that LNG can impair the development of the fertilised embryo or prevent implantation, but any post-fertilisation action cannot be completely excluded. However, it is clear that LNG does not disrupt an established pregnancy, defined as beginning with implantation, and is not considered an abortifacient.10

Who uses emergency contraception?

Information about the users of EC is conflicting, with some studies showing more users to be young and unmarried, while other studies have found more users to be older and in stable relationships. Similarly, findings as to whether users are at high risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancy more generally, have differing findings.11 An Australian study of sexual health clinic clients requesting EC found users were more likely to be a student, to have a regular sexual partner and less likely to have had an STI or previous unplanned pregnancy than controls.11 It is clear that it is not accurate to stereotype the EC user as young, irresponsible and at risk of STIs, which seems to be a common perception.

Wide access to emergency contraception – what happens?

There has been considerable debate internationally over widening access to EC, including the concept of advance provision. From a public health perspective, wider availability has been supported by numerous reproductive and other professional health organisations, as it seems logical that ready access to EC should reduce the number of unplanned pregnancies, along with the rate of abortions. Detractors have voiced concerns that wide access might result in reduced use of regular contraception, encourage irresponsible behaviours and increase STIs. Evidence, however, does not support either of these suggested outcomes. While increased access to EC pills improves use, disappointingly, it has not shown in a systematic review to have a population effect12, although there are no published population studies in the Australian context.

A Cochrane review found advance provision of EC did not reduce pregnancy rates when compared to conventional provision and this ready access did not change the use of regular contraception or sexual behaviours.13 Random controlled trials (RCTs) have been consistent with this encouraging finding (that ready access to EC does not negatively impact on sexual and reproductive health behaviours and outcomes), including studies specifically with teenagers.14,15 Follow-up at three years from a large trial, where 17,800 women had access to home supplies of EC in Scotland, found that routine use of more effective contraception actually increased amongst these women.

It seems that even when women have ready access to EC, including advance supply, they often don’t use it after uPSI, most commonly due to a lack of recognition of the risk of pregnancy or a neglect of the perceived risk.13 Of 518 women seeking abortions in a Swedish study, 83 per cent knew of the ready availability of EC, but only 15 had used it to attempt to prevent the current pregnancy.16 The available data suggest abortion rates have remained unchanged for complex reasons, where women at risk for unintended pregnancy fail to use it when it is indicated.8

Barriers to emergency contraception use

Knowledge

Numerous studies have explored the levels of community knowledge about EC, but less is known about the situation in Australia. Two Australian studies found significant EC knowledge gaps amongst tertiary students in Adelaide17 and Cairns18, including poor understanding of the recommended timeframe, low levels of knowledge of the current ‘over the counter’ (OTC) status and misunderstandings about the mechanism of action. Many women also had poor knowledge of fertile times seeking in their cycles meaning they are not well able to assess their pregnancy risk after uPSI.17 There has been little research in Australia on clinician knowledge, but studies from other countries suggest that clinicians have poorer than expected knowledge about EC. Poorly informed clinicians are unlikely to provide opportunistic education and advance provision to the women who could benefit from this information and opportunity for future access.19

Provider and cost issues

While OTC supply has the potential to increase access generally at a population level, for individuals, pharmacy EC supply may add some specific barriers. Little has been published in the Australian situation, although it is of concern that more than 20 per cent of tertiary students in the Cairns study felt unable to purchase EC in a pharmacy where they may be recognised.18 While pharmacies are required to provide a designated private counselling area, in reality, this space may feel less than private to many women seeking EC. While most pharmacists have embraced the Schedule III listing and see EC supply as an extension of their role in the healthcare team, some women report seeking pharmacy supply as being confronting and difficult experience. These perceived barriers are likely to be even greater in secondary age students and marginalised groups. While a prescription is not required for EC, an advance prescription by a medical practitioner (which will then be dispensed by the pharmacist without need for a pharmacy ‘supply consultation’) is one strategy which could help overcome some perceived barriers for women.

EC is not Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) listed and may sell for upwards of A$40 in some pharmacies, which may be a disincentive to its use for some women. Doctors can prescribe a PBS listed 30mg progestogen ‘minipill’ (for example, Microlut®) and advise on the ‘25 pills and repeat in 12 hours’ regimen as used off label pre 2002. For a healthcare or pension card holder, a single script will give two EC treatments for approximately A$5.

Conclusions

While we have come a long way with EC in Australia in terms of an available OTC dedicated product, there are still significant barriers to its use. While at a population level, international studies have not found that wide availability decreases unplanned pregnancy, it does not result in decreased use of regular methods or behaviour changes which would adversely affect other reproductive or sexual health outcomes. While complex factors unfortunately seem to prevent women taking EC, even when there is ready access, they won’t have the chance to even consider its use if they misunderstand it or don’t know about it at all. EC is a woman’s last opportunity to prevent an unwanted pregnancy. Clinicians in Australia have a responsibility to inform women about emergency contraception and consider the benefits of offering an advance prescription to sexually active women not using a long-acting contraceptive method.

References

- Task Force on Post-ovulatory Methods of Fertility Control. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regime of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet 1998; 352:428- 433.

- Sexual Health and Family Planning Australia. Contraception: An Australian Clinical Practice Handbook. 2008. SHFPA, Canberra.

- von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimes of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 360:1803-1810.

- Trussell J, Ellertson C. Efficacy of emergency contraception. Topical reviews. Fertility Control Reviews 1995; 4:8-11.

- Cheng L, Gulmezoglu A, Piaggio G, Ercurra E, Van Look P. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008, Issue 2.

- Glasier A, Cameron S, et al. ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception:a randomised non inferiority trial and meta analysis. Lancet 2010. Online 29 January.

- Baird D. Emergency contraception:how does it work? Ethics, Biosciences and Life 2009; Vol 4,No.1.

- Greene M. Emergency Contraception: A Reasonable Personal Choice or a Destructive Societal Influence? Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2008; Vol 38, No.1.

- Piaggio G, von Herzen H, Grimes DA, et al. Timing of emergency contraception with LNG or Yuzpe regimen. Task force on post ovulatory methods of fertility control. Lancet 1999; 353:721.

- Allen R and Goldberg A. Emergency Contraception: A Clinical Review. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2007; Vol 50, No.4, 927-936.

- Fox J, Weerasinghe D, et al. Emergency contraception: who are the users? International Journal of STD & AIDS 2004; 15,5:309-313.

- Raymond E, Trussel J, Polis CB. Population effext of increased access to emergency contraception pills: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 109:181-188.

- Polis C, Grimes D, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007; Issue 2.

- Ekstrand M, Larsson M, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraceptive pills reduces treatment delay: a randomised controlled trial among Swedish teenage girls. Acta Obstetricia and Gynecologica 2008; 87:354-359.

- Gold M, Wolford J, et al. The effects of advance provision or emergency contraception on adolescent womens sexual and contraceptive behaviours. J Pediatric Adolesc Gynecol. 2004; 17:87-96.

- Aneblom G, Larsson M, et al. Knowledge, use and attitudes towards emergency contraceptive pills among Swedish women presenting for induced abortion. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 109,155-160.

- Calabretto H. Emergency Contraception – knowledge and attitudes in a group of Australian university students. ANZJPH 2009; 33,3:234-238.

- Mohoric-Stare D, de Costa C. Knowledge of emergency contraception amongst tertiary students in far North Queensland. Aust and New Zealand Journal Obstetrics Gynaecology 2009; 49:307-311.

- Broekhuizen F. Emergency contraception, efficacy and public health impact. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;21:309-312.

- Trussell J, Rodriguez G, Ellertson C. updated estimates of the effectiveness of the Yuzpe regimen of emergency contraception. Contraception 1999; 59, 147-151.

Leave a Reply